There were two weeks at the tail end of April when I didn’t publish. I chalked up my daily struggle to get through those days—out of bed and onto my waterlogged to-do list—as a matter of sheer exhaustion. I’ve just begun my fourth third trimester in five years. I have been travelling a lot—back and forth from Europe, then home for the holidays, then Maryland for a friend’s 30th birthday. There are obvious reasons to be tired.

I’m usually revived by a good workout, a hot bath, and a solid night’s sleep. But I’d been finding it unusually hard, even with the usual methods, to kick myself into gear. After a few days of playing Sisyphus on the treadmill, the thought occurred that at this time last year, we found out that the back pain my mother had been feeling for a few months was actually cancer.

At first, they thought bone cancer. More specifically, multiple myeloma, judging by the tumor lodged in her sacrum. But then the biopsy revealed a cell pathology consistent with breast cancer. Strange, since she’d had a squeaky clean mammogram not even a year prior. Another mammogram revealed nothing in her breast. It must have cannibalized itself? The doctors used terms like “medical mystery.” They also used “metastatic,” but she didn’t let us say that one aloud.

Google told me she could have years. I clung, white-knuckled, to false hope. She got weeks.

Despite laboring against the creeping despair that twists like vines around my ankles if I stand still for even a moment, the body demands rest. This reversion to an infantile inability to identify and articulate and then meet my own needs—most acutely at the moment of Mom’s death, and then sporadically throughout the year, in moments like these—has been one of the more jarring aspects of grief. I wrote about the physicality of it all before.

Much like an infant, I have the profound sense that I was carried through this past year, by the Holy Spirit acting through the set of surrogate mothers that I inherited in the form of Mom’s friends. These women helped facilitate an extraordinary funeral. They call me regularly. They take care of my children. They help me remember her. They offer a soft place to land and firm encouragement when it is needed. For every major holiday since, my children have not gone without a grandmotherly sprinkle of magic. She cannot be replaced, but then again, the language of replacement is limited in itself. Human beings aren’t fungible. The mysterious grace of grief is that new opportunities to love people in new ways often open up in the wake of tragedy. My mother’s motherhood journey was not terminated when she died; it was transmuted.

I read a piece here on Substack on the morning of Mother’s Day with the precis “don’t ruin Mother’s Day by insisting on celebrating non-physical mothers.” The author cites “spiritual motherhood” as one of the ways that people “stretch the definition of ‘mother’ until it’s basically meaningless.” It was written by a man, a popular millennial evangelical pastor, and I’ll try not to hold that against him. Perhaps he believes he’s standing up for his wife against stolen valor vultures. A more choleric (and honest, honestly) version of me interprets the essay within the broader context of the ritualistic, woke / counter-woke dialectic, as just another cheap, virtue signaling spar in the clickbait battle that has come to define every cultural event in this country for years. He’s not alone; a similar sentiment echoed through conservative media, predictably.

To be fair, the other side fired the first shot. The defining spirit of the left, broadly speaking, and the thing that really put me off of contemporary liberalism, is this incessant and indiscriminate destruction of meaningful distinctions: between the sexes, between cultures, between religions, between countries, between categories of excellence. I think it’s best understood as an undisciplined overemphasis on the principle of universality. Over time, many came to the conclusion that a rigid and imprecise overcorrection is the only appropriate answer to global homogenization. And I get it. A natural, maybe even noble, “fuck you” rises in a person’s chest when you deny the importance of the things, however provincial or idiosyncratic by cosmopolitan standards, that are most important to them—or when you cruelly deny their right to celebrate life as they see fit, in the ways that are culturally salient to them. Particularity matters.

It’s also true that we could do away with most of the politically correct throat-clearing in corporate Mother’s Day emails. But if any holiday deserves a gentle and generous touch, especially on the interpersonal or pastoral level, it’s this one. To reject the principle of motherhood beyond the physical such that we bury women who have experienced loss in the context of the mother/child dyad—of their own babies, of their mothers, of imagined futures or stolen pasts—betrays not only Christian charity but ironically the very thing that OP claims he wants to preserve: the truth.

Spiritual parenthood—whether motherhood or fatherhood—is not a cheap consolation prize for infertile or single people. It is a deep spiritual reality. The fact that it escapes the rational searchlight of modernity does not mean it does not exist. The Catholic Church gave language to this reality in the titles used for male and female leadership in clergy a long time ago. Most importantly, so did Christ, when He emphasized the fatherhood of God (not just in the particular sense of the trinity, but as a universal Father) as well as the motherhood of Mary to John the Apostle in the moment of His death (John 19:25-29).

But in general, for modern people, the default scientific-materialist mode of interpreting reality denies the spiritual dimension outright. Emotions are reduced to mere chemical reactions. Love is merely an attachment style. Virtue, if we can speak of it, refers to behaviors that confer evolutionary advantage. Technology frees people from nature, and to extent intuition remains, it is but an accidental vestige of our animalistic past. Regardless, everything points back to selfish survival in the end.

Even where re-enchantment reigns, whether in neoreactionary traditionalist religious communities or crunchy new age covens, there remains the mechanical tendency to flatten archetypes into rigid, pseudo-scientific, false dichotomies that, when applied in real life, can unfold in even more painful and dehumanizing ways than the greige nothingness of globohomo.

Another impediment to understanding spiritual motherhood and fatherhood is that this is essentially a discussion about spiritual maturity, the development of virtue in men and women in particular, but particular virtues do not belong to one gender or the other. Modes of expression may vary, and indeed indicate something of the richness of God’s imagination, but the unifying principle is unchanged. Men and women are different, and yet we are both created in the image of God. Despite superficial contradictions, universality and particularity are both true… and good… and beautiful. Holding space for this tension is perhaps uniquely difficult for a mind formed by the internet, with all its structural preferences and incentives for high-contrast, black-and-white thinking.

For Edith Stein, the Jewish philosopher turned Catholic nun, who was martyred in the Holocaust and canonized as St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, spiritual parenthood is the ultimate vocation of both sexes, made clear through God’s relationship to us as Creator:

We are led through the imitation of Christ to the development of our original human vocation which is to present God’s image in ourselves: the Lord of creation, as one protects, preserves and advances all creatures in one’s own circle; the Father, as one begets and educates children for the kingdom of God through spiritual paternity and maternity.

The beauty of motherhood in particular is to Stein the interior disposition toward the formation and flourishing of the most vulnerable: to be able to intuit the hidden needs of precarious life and cultivate from that point. To be clear, it’s not that men are incapable of or absolved from the responsibility to identify the humanity in the weak. In fact, Stein writes in another essay about how men and women both have the responsibility to educate themselves in the virtues that come more naturally to the opposite sex. She never fails to acknowledge great variation in individuals, too. Still, women, made evident through their physical nature, have a special talent for tenderness. Spiritual motherhood is being able to hear the inaudible, see the invisible, and move, often inaudibly and invisibly, to take care:

Spiritual motherliness [is] not limited to the mother [relationship], but extend[s] to all people with whom woman comes into contact. The soul of woman must therefore be expansive and open to all human beings; it must be quiet so that no small weak flame will be extinguished by stormy winds; warm so as not to benumb fragile buds; clear, so that no vermin will settle in dark corners and recesses; self-contained, so that no invasions from without can peril the inner life; empty of itself, in order that extraneous life may have room in it; finally, mistress of itself and also of its body…

The women who now mother me in my mother’s absence do exactly what Stein describes. They intuit the need, tend to the invisible wound, and offer protection without fanfare. Their generosity has been a balm and a lifeline. For this, I owe them a gratitude that feels almost indistinguishable from what I feel for my own mother—who, I know, would bless it. She would have seen stinginess in gratitude as an affront to reality itself. Love is not zero-sum.

As Michael Pakaluk so beautifully put it: “Stein teaches us that true motherhood is metaphysical, of which the biological is an image. The unseen reality is greater. All women are called to realize it. True motherhood is a matter of corresponding to a spiritual vocation.” Alice von Hildebrand, in an interview compiled by Plough, said along the same vein: “Spiritual motherhood is more important than biological motherhood. There are plenty of women who are biological mothers and yet are not mothers at all. Some consider their child to be a nuisance and an accident, saying ‘I didn’t want it.’” There are just as many women who are not biological mothers and, yet, in every meaningful sense, are mothers.

Aside from the unspeakable mystery of our proximity to the veil, the parallels between birth and death are striking. Our worlds are, in a sense, recreated with every birth and every death. Both involve surrender, intimacy, passage, and, often, on the earthly side, some kind of midwifery. So in both spaces, we tend to find women. It reminds me of the Dorothy Sayers quote from Are Women Human?

Perhaps it is no wonder that women were first at the Cradle and last at the Cross. They had never known a man like this Man – there never has been such another. A prophet and teacher who never nagged at them, never flattered or coaxed or patronised; who never made arch jokes about them, never treated them either as “The women, God help us!” or “The ladies, God bless them!”; who rebuked without querulousness and praised without condescension; who took their questions and arguments seriously; who never mapped out their sphere for them, never urged them to be feminine or jeered at them for being female; who had no axe to grind and no uneasy male dignity to defend; who took them as he found them and was completely unself-conscious. There is no act, no sermon, no parable in the whole gospel that borrows its pungency from female perversity; no one could possibly guess from the words and deeds of Jesus that there was anything “funny” about women’s nature.

In the first and final things, womanhood reveals its most tender and essential form. This is the heart of spiritual motherhood. Even the death of our physical mother will not render us motherless. Among other things, spiritual motherhood serves as a guardrail against the abyss of despair that is the Mom-shaped hole in the heart of a motherless person. Because of the reality of spiritual motherhood, alienation from our physical mother need not render us abandoned. By the same token, alienation from our children, whether by infertility or circumstance, need not render us spiritually barren.

A cynical critic might minimize the role of my spiritual mothers as a mere psychological coping mechanism, but what a lifeless and limiting vision of love that would be. On Mother’s Day, I think it is worth remembering that God’s imagination transcends human categories of understanding. The only thief here is time.

May the souls of the faithfully departed, through the mercy of God, rest in peace.

Beautiful, Helen. I am so sorry that your mother is not here. My mom, unfortunately, was also in the "back pain reveals metastatic medical mystery" club and died when I was 18. Your words about birth and death remind me that in her final days, as I sat beside her, she told me about two visitors in the room who I couldn't see: her mom, and Jesus. Their presence gave her comfort. When I was in my final days of pregnancy with my daughter, I followed suit and liked to picture my mom and Jesus with me, offering support and strength for labor and birth.

Sometimes I dwell on the fear of what would happen to my daughter if I die young. I have to remind myself of the merciful God who has sustained me, and the spiritual mothers who have held me and, as you write, not left me abandoned. I simply have to trust that He would do the same for her.

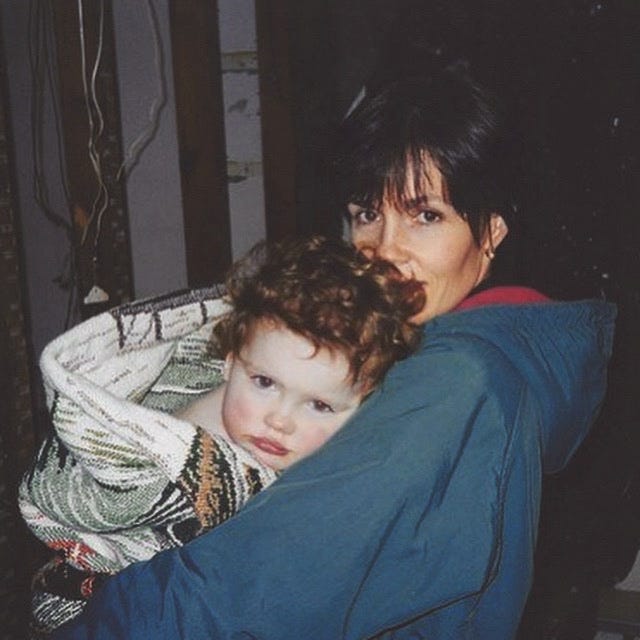

Thank you for writing this and for sharing the sweet photos! Praying you feel your mom with you as you get ready to welcome your newest little one.

I really appreciated this read, for both its capacious understanding of woman and of personhood ("the development of virtue in men and women in particular, but particular virtues do not belong to one gender or the other..." girl, PREACH) and its compassion for the childless/motherless. As someone experiencing infertility, I felt a real sense of renewed possibility after reading this piece. If you have a booklist for the various thinkers you mentioned, I'd love to read more deeply.